How to build successful products your customers want to buy

Phillip Kotler, marketing professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, defines product like this:

A product is anything that can be offered to a market for attention, acquisition, use or consumption. It includes physical objects, services, personalities, places, organizations, and ideas.

It's fascinating how broad the definition is. Tweets, LinkedIn videos, shoes, the location of my favorite café, and even this post are products by Kotler's definition.

And I think that's fitting, because there's much more to a product than simply the item on the shelf.

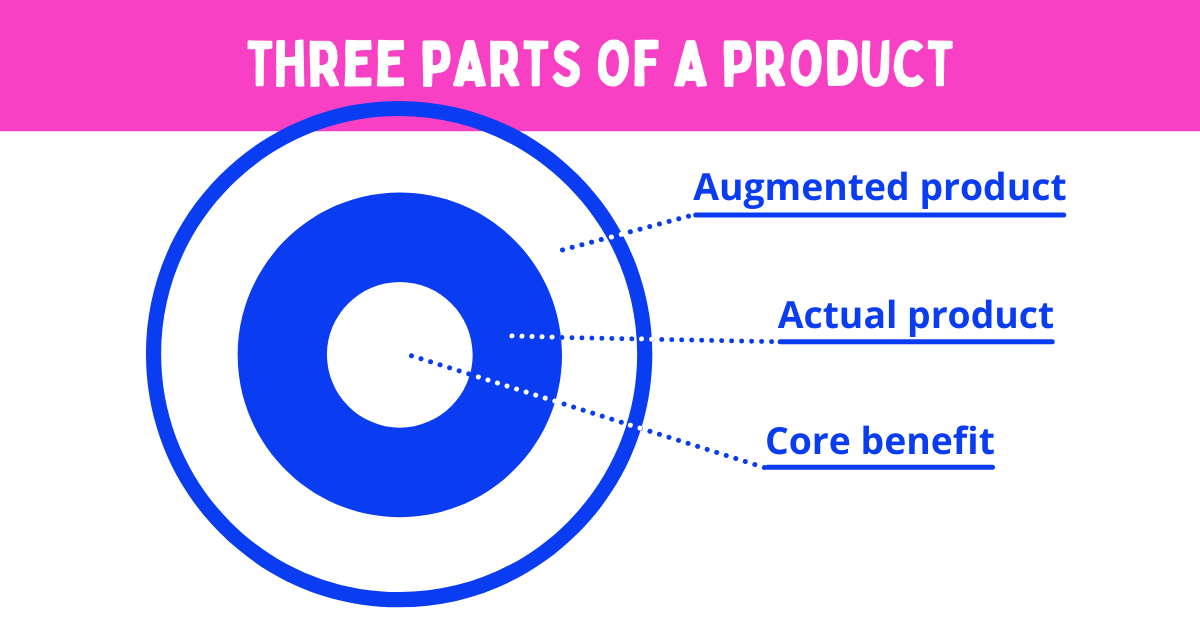

The three parts of a product

Every product is made up of three parts:

- The Core Product is not the physical product or service. The Core Product is the primary benefit a consumer receives. This surprised me, but if you look at the benefits ladder of a product, the Core Product is the same as the Core Benefit.

- The Actual Product is the physical or other tangible aspects of the product or service. The product itself, not the perceived value and benefit of the product, is the second part we need to pay attention to.

- The Augmented Product includes everything that makes it possible to experience the actual product. From how it's delivered to after-sale service, the product experience does not start or end with the product itself. I love this concept.

I haven't paid enough attention to parts 1 and 3. I focused too much on the actual product and given too little time to defining the core benefit. As for the augmented product parts, I only went as deep as acknowledging that I (or the companies I've worked for) had to provide excellent service after the sale.

What a customer buys versus what we sell

By not paying enough attention to the core product or the augmented product, it's likely that customers buy something different from what a company thinks it sells. There's opportunity in closing the gap between what a customer believes they're buying and what a company thinks it's selling.

Here's a personal example of how I created a gap between what I thought was my product and what customers were buying.

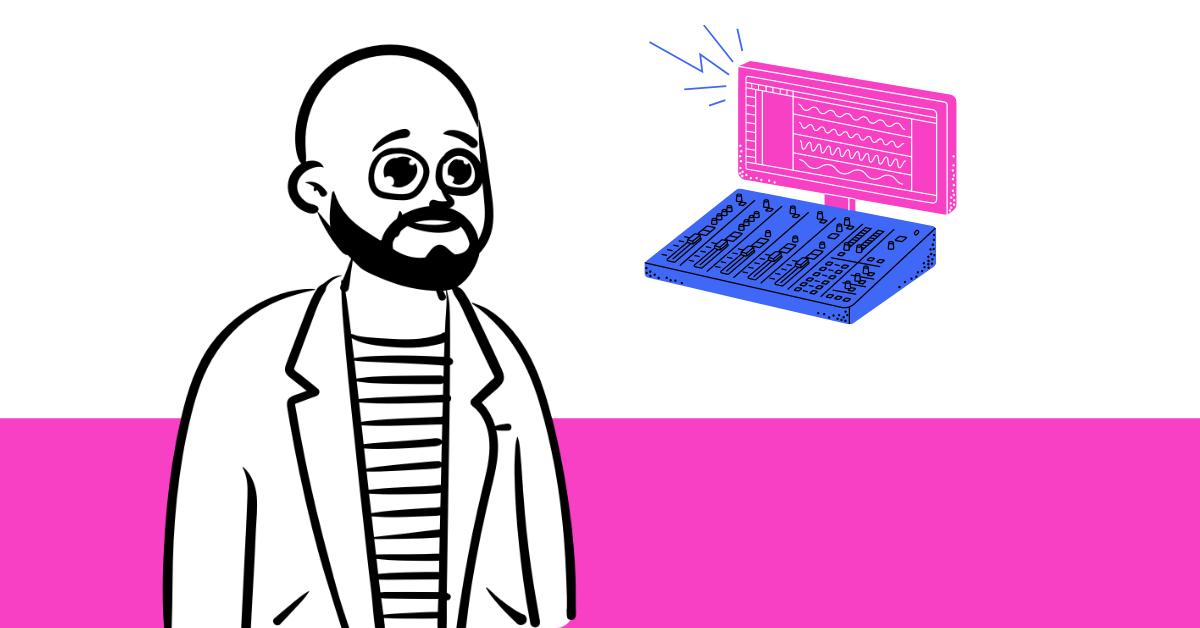

A story about a video editing service

I built and ran a video editing service called Dear Video for a a little over a year. It was a joy to build a team and a service and to find customers in a creative field.

I thought I was selling video editing services - the actual product. What I realized after talking to customers is that they weren't buying the video editing service. They were buying their time back. They were buying the process that made it easy to request a new edit and get a final product without spending much time on it. They were buying the ability to produce more work in less time.

By uncovering those three parts of the product, Dear Video becomes more than a video editing service. The product is an easy and cost-effective way for in-house video producers to make more video and build their brand faster without hiring.

It's hard to know what you're selling

The moment I become a marketer or a producer, I'm not longer the consumer and I can't understand what a consumer wants and needs. I'm too biased. And that's ok, but it does make it hard to understand the difference between what I think I'm selling and what my customers are buying.

That's where Jobs to Be Done comes in.

Jobs to Be Done and understanding customer needs

In their 2016 article Know Your Customers’ “Jobs to Be Done”, Clayton M. Christensen, Taddy Hall, Karen Dillon, and David Duncan highlight how product developers need to think about their customers. Instead of focusing strictly on personas:

To create offerings that people truly want to buy, firms instead need to home in on the job the customer is trying to get done.

Product owners have to ask what customers are "hiring" a product or service to do for them. Answering this question gets you closer to understanding how you can help customers and ultimately sell to them. Including this "hiring" information in buyer personas will make them that much more useful.

So, what does it mean to hire a product to do a job?

A job is what people want to accomplish

When I was working with ThinkTilt, the makers of ProForma for Jira, our primary product was a Saas form builder add-on for Jira. People found us by searching for a form builder because they were already experiencing pain: our customers used Jira to collect information from people. Jira is a great product, but the ability to ask questions and collect answers was limited.

Customers hired ProForma to create structured forms that ask the right questions and prompt the right answers. Customers bought ProForma to get them better answers and better data to save heaps of time and dramatically cut down on back and forth email and chat messages. When a large company can reduce the volume of internal communication by 70%, that's a lot of time and value they get from a form builder.

Once we realized this was what people were hiring us for, we doubled down on that messaging. We shifted from talking about what we thought were the benefits to talking about how quickly customers' work could get done and how much less work they would have to do. That's when growth took off.

Designing products around jobs

In the example above, we had a product and we needed to figure out what job it performed for people. Imagine if you could start with that understanding before you build a product? The odds of that new product succeeding must be higher, right?

By understanding customers' problems and how they address them now, you can start to understand where current solutions fall short. And you can build products to do the job better. A well understood job to be done is like a job spec. If you start with the job in mind and build your product to deliver that, boom! You're on the path to helping people and selling some serious product.

Jobs to Be Done is a great framework for understanding what a product can do for customers. Now let's look at ways to move beyond a single product and leverage your growing brand.

Product diversification for growth

There's nothing wrong with selling more of a single product. But what about adjacent opportunities to grow? Product diversification offers brands a way to leverage current momentum for growth.

There are three major ways to diversify products:

- Line extension

- Brand extension

- Co-branding

Line extension

Line extension keeps you within your existing category, but lets you look up and out. Maybe you've identified a growing or new target segment you'd like to cater to, but your current products don't quite fit. A line extension allows you to create new products that fit into this new segment.

Flanker brands are created on the side to target these new segments without damaging your existing brand's market share. Companies employ flanker brands to protect against competitors attacking the main brand. A good example of this is Intel's Centrino processor, a lower-cost brand launched to protect Intel's more expensive Pentium brand.

Flanker brands don't have to be cheaper version of what already sell. They can be premium products offering higher quality at a higher price. Luxury brands use premium offerings as a way of anchoring their overall brand value. For example, a luxury watch brand may launch an exclusive watch for $100,000. Products like this bring a lot of attention and raise the value (aka a "halo effect") of the overall brand. And all of a sudden, the $10,000 watch sitting next to the $100,000 watch seems like a bargain.

Fighter brands are line extensions built to take on lower cost competition. When Virgin Blue (now Virgin Australia) launched in 2000 offering lower cost fares, the flagship Australian airline Qantas responded by launching Jetstar, another value-based airline, to compete with Virgin and protect Qantas' overall market share.

Brand extension

Brand extensions are a way for an established brand to bridge the gap between two product categories. Using existing brand equity and associations, a well-established brand may launch products in new categories.

Some examples of brand extensions include:

- Ferrari went from an exotic sports car category to theme parks with Ferrari World in Dubai

- Google went from search engine to email service, document creation and more

- Colgate went from toothpaste to toothbrushes

- Honda went from motorcycles to cars to lawnmowers

- Cadbury's went from high-end chocolate to instant mashed potatoes (terrible idea, but still an example of brand extension)

Not all brand extensions work. The Cadbury's example above was a flop - and why the hell wouldn't it be? My take on this is that a brand extension should relate to the overall brand by some narrow measure. In the Cadbury's example, chocolate and mashed potatoes are both food items. But that's too broad. Moving from chocolate bars to chocolate cocktails makes a lot more sense.

A note on brand extension vs. line extension

Brand extensions are less likely to succeed, but are also very unlikely to damage a brand. Brand extensions are not products in the same category a brand is known for and because of this there is limited impact on the main products and brand if the new extension products don't perform well.

Line extensions are far more likely to succeed in financial terms, but they also carry much more risk to the primary brand. Line extensions are products in the same category a brand is known for and because of this it's easier for consumers to associate performance back to the original products and brand.

Both brand and line extensions should be carefully considered.

Co-branding

When two (or more) companies come together to develop and launch a product, that's co-branding. There are many advantages to co-branding and when done well it can boost sales, generate tons of exposure, and help both companies learn from each other's.

When done well, co-branding often leads customers to assume that both brands bring their best qualities to the new product.

GoPro and Red Bull teamed up on Stratos, Felix Baumgartner's unreal and totally amazing 24-mile skydive. This cross-over worked because these brands share similar values of reimagining human potential.

Adidas and Kanye West came together to produce a high-end line of kicks called Yeezy. Kanye's celebrity combined with Adidas's streetwear segment generates millions in revenue and who knows how much more value in brand perception.

Co-branding allows you to reach different market segments, try different positioning, build synergy (yes, I said synergy unironically) with another brand, and allows you to leverage a different core competence to bring legitimacy to new products.

There's so much more to product creation

From figuring out which products to create and who to create them for to avoiding new product failure to conducting Net Promoter Score (NPS) surveys, there's way more to product development and creation than I could fit into one post. This one is probably too long already.

A related topic is knowing when to kill off products and features. I explore unshipping features here. If I write on removing entire products, I'll link that here too.

Marketers have a place in product development: 3 takeaways

- There's more than meets the eye when it comes to product. Marketers have unique insight into how customers perceive a product and we need to share that insight with product teams.

- The Jobs to Be Done framework helps us understand why customers buy products. Including those jobs in buyer personas is a strong way to keep the focus on what the customer is actually buying.

- There are three ways to diversify products and as marketers we should be on the lookout for opportunities to expand our footprint in the market.

This is just one post in a series on marketing strategy. Here are the rest:

- How epic companies like Nike and Amazon grab advantage with market orientation

- How to do market research for a startup (from a Saas product marketer)

- Market segmentation? Unwrap the best way to nail your marketing strategy

- Your next market targeting strategy must highlight these two things

- Positioning (coming)

- Objectives (coming)

- Product (coming)

- Pricing (coming)

- Integrated Marketing Communications (coming)

- Distribution (coming)